Schworer, an assistant professor of rheumatology, allergy, and immunology and the UNC School of Medicine, wants to know how lung tissue becomes asthmatic, in the hope of preventing the disease from developing. Breathing trouble can quickly lead to coughing, wheezing, and chest tightness.

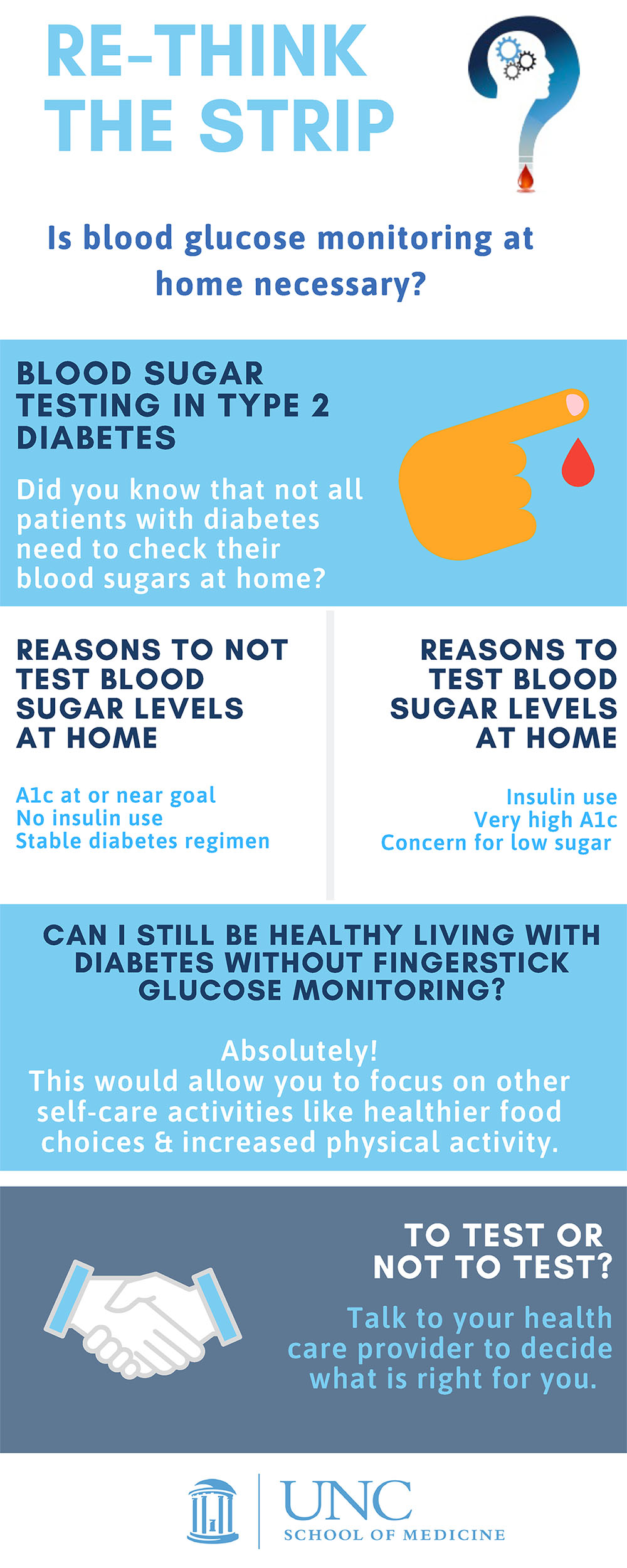

Re-thinking diabetes testing

UNC researchers are teaming up with local healthcare clinics to eliminate unnecessary daily testing for some diabetes patients.

A new diabetes diagnosis can be scary. Suddenly, you can no longer trust your body to regulate its own blood sugar and need to balance diet, exercise and medication to prevent your glucose levels from being too low or rising too high. To help keep that plan on track, many people with diabetes prick their finger and test a little drop of their blood every day to know: Am I too high? Too low? Or just right?

But what if they don't need to do that? After all, the cost of the equipment and supplies needed to test glucose levels can add up over time—and there are other ways to track how well a person is managing their diabetes, like an A1C test, which shows average blood sugar over the past three months.

In 2017, a group of researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill published a study that came to a potentially surprising conclusion. In people with Type 2 diabetes who were not taking insulin, patients who regularly monitored their blood glucose levels seemed to be managing their disease just as well as patients who didn't regularly monitor their blood glucose levels. And this paper isn't alone.

Katrina Donahue, MD, MPH

"We have multiple trials that show that, for patients who don't take insulin, daily blood glucose testing doesn't improve long-term health," said Katrina Donahue, a family medicine researcher at UNC.

Donahue was on that 2017 paper as part of her work with the North Carolina Network Consortium (NCNC). NCNC, which the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute supports and helps to organize, is a practice-based research network. They work with researchers at multiple universities in North Carolina, as well as clinicians at medical practices across the state to answer important questions in primary care medicine, with the goal of helping everyday patients get better care.

That mission is why the NCNC took on the question of daily glucose testing: if millions of people were buying test strips and pricking their fingers unnecessarily, we'd want to know. The NCNC team has now embarked on a project they call "Rethink the Strip"—tapping into their extensive network of clinicians and researchers across North Carolina to share the findings of that 2017 study and figure out how to get people to stop regular glucose testing.

"How do we de-implement something that we've always done?" Donahue asked.

Practice-based research networks (PBRNs) like NCNC are designed to answer this kind of question. While traditional medical research is centered around research hospitals and universities like UNC, practice-based research takes place in a variety of clinics, including practices in rural areas far from the hospital. NCNC includes five PBRNs from across North Carolina, including NCnet, a network of researchers and providers centered at UNC, as well as PBRNs organized through Duke, East Carolina School of Medicine, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, and Mountain Area Health Education Center.

This set-up is a two-way street. For academic scientists, PBRNs can help them recruit patients from a variety of different backgrounds, not just the people who come in for treatment at their main hospital. "If we're studying the same patients time after time after time, it's not really a good representation of the patients or the people of North Carolina," said Jen Rees, practice facilitator with NCNC. "So doing the work that we do, I think is better, sound science."

Jennifer Rees, RN, CPF

By taking their work out into these clinics, these researchers can get a better sense of whether their ideas are feasible in real-life healthcare clinics where many people are treated and seen by physicians. For example, suppose a researcher has an idea to help diagnose a disease more accurately. Maybe that idea sounds great on paper, but it requires technology that most clinics don't have—making it relatively useless for the providers working in these clinics.

Often, researchers plug into NCNC through NC TraCS—Rees called NCNC the "gateway" between TraCS and community-based practices. The NCNC team can also consult and mentor researchers who are interested in practice-based research.

For clinicians at these practices, being in a PBRN can bring cutting-edge medical research to their practice, giving their patients the chance to be a part of new studies. "Patients in these clinics have the same diseases that everyone close to the hospital does," Rees said. "They have diabetes. They have hypertension. And a lot of times, those are who we really want to reach out to, because they aren't getting all the new and improved methodologies as patients at big hospitals might be getting."

Rees works to recruit practices and get them involved in research, reaching out with information on NCNC and answering any questions the local clinicians might have. Often, she'll even pack up some up lunches and bring them out to the clinic to meet with their staff in person. In addition, Rees helps the practices understand what their role in the research process would be, makes sure they have what they need to get involved, like space to store samples, and explains that the research team will usually provide any equipment or staff needed to undertake the data collection.

Clinicians at these practices can also use the PBRN to help find answers to questions they think are important, and some of the clinicians in their network have been authors on studies published by the NCNC team. And for many clinicians, connecting into a PBRN can even be a way to earn continuing medical education (CME) credits. Healthcare providers need to take a certain number of hours of CME each year, and Rees says her lunch and learn sessions, for example, can count.

All of this helps create a fruitful, long-term, and mutually beneficial relationship between clinics, researchers, and the NCNC team. "Bottom line, I think relationships matter," Donahue said.

This series of studies on diabetes, a disease commonly addressed by primary care doctors, was a natural fit for NCNC's research model. For years, there had been evidence building that some patients with diabetes may not need to be testing every day. That led to the team's initial paper in 2017, which found that, for patients with Type 2 diabetes who were not on insulin and were generally controlling their diabetes well, there was little benefit to testing every day.

It's not as if patients who forgo daily testing have no way to keep track of their diabetes—whenever they get their A1C test, that can indicate their average glucose levels over the past three months, allowing them to adjust diet or medications as directed by their physician. "You're going to get that information every three months, as opposed to doing it every day and not getting anything for it," Rees said. "And do you really want to prick your finger every day, or twice a day, or three times a day? And the expense of that?"

Plus, there are some potential drawbacks to testing every day, notably the cost of buying test strips. Donahue noted that some patients might also be more inclined to eat things they shouldn't be eating if they get a good glucose reading. "Some patients could say 'Oh, okay my blood sugar is fine, I'm going to eat this cupcake," she said.

Patients in [rural] clinics have the same diseases that everyone close to the hospital does... those are who we really want to reach out to, because they aren't getting all the new and improved methodologies as patients at big hospitals might be getting."

"Using your blood glucose to determine what your diet should be for that day is not the right thing," Rees added.

After their 2017 study was published, Donahue, Rees, and their colleagues started thinking about how to encourage healthcare providers to stop encouraging daily glucose testing, and how to convince patients to stop daily testing themselves. They designed a multi-pronged gameplan to tackle this question—which they called "Rethink the Strip"—and set out to study how well that program might work at 20 different clinics across the state.

Rethink the Strip efforts include outreach to providers, like hosting lunch-and-learn sessions and recruiting "champions" among the staff at each practice to encourage them to de-implement daily glucose testing with their patients. To help these practices prepare for potential questions and concerns from their patients, the team looked at the comments on a story in The New York Times on their original 2017 paper to see what people had said about the idea of stopping daily testing. They also created literature for patients to get them to talk with their doctor about the idea.

Earlier this year, the team published a paper documenting some of the initial impact of this program. Twelve months after Rethink the Strip efforts began, patients at these clinics were receiving fewer prescriptions for diabetes testing supplies. That said, the prescription rate also dropped at clinics that didn't go through the Rethink the Strip program, which they used as a comparison to test their program.

Among new patients—either patients who had just been diagnosed with diabetes, or patients who were new to those clinics—the prescription rate at Rethink the Strip clinics dropped (from 20.9 percent to 16.6 percent) significantly more than at other clinics (which dropped from 19.3 percent to 16.7 percent). But after a year and a half, this difference between Rethink the Strip clinics and other clinics was not statistically significant, and new patients were actually more likely to receive a glucose testing prescription after a year and half at both groups of clinics.

This study helped prove a time-worn adage—old habits can sometimes be hard to shake. One challenge was that this study took place during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many patients were seeing their doctors less frequently, and may have wanted more tools to keep track of their diabetes at home. In addition, all the clinics already had relatively low levels of diabetes test strip prescriptions at the outset, at just around 30 percent.

But this study has helped the NCNC team think about where to go next, like what roadblocks might exist to de-implementing regular testing, how to work with patients and other stakeholders, and how to share their results.

Li Zhou, the medical director of the UNC Knightdale Family Medicine clinic, has worked with the NCNC team for years on multiple different projects, including Rethink the Strip. She says that while some of her patients aren't interested in being a part of this kind of research, some are—and are grateful to hear that they don't have to poke their finger every day to stay healthy.

Zhou notes that the number one rule in medicine is "Do No Harm." She says that as clinicians, they have to make evidence-based decisions, use new technologies—and empower their patients to reduce costs.

The relationships between researchers, clinicians, and patients that NCNC has developed over the years will continue to guide this work. Rees points out that many of the clinics who were involved in the research for the team's original 2017 paper were also involved in this latest study. "They could see how their interaction with the research team was effective, that they were part of answering the question," Rees said.

"They can see how important research is to the practice, but also to their patients, and what the patients are getting out of it. So, I think that helped make it successful."

NC TraCS is the integrated hub of the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that combines the research strengths, resources, and opportunities of the UNC-Chapel Hill campus with partner institutions North Carolina State University in Raleigh and North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro.